and some of the lessons software engineers can learn from grid operators.

#bangbangcon2020 #virtualbangbangcon #electrical-grid #distributed-systems

#failure-analysis #safety-engineering #infrastructure

- !!con 2020 @ YouTube Virtual Conference on 2020/05/09

- Center Camp lightning talks 2019 @ Black Rock City: on 2019/09/01

Quebec built the world's first 735 kV power line in 1965, and was the highest-voltage, longest-distance network for decades before the rest of the world caught up. Even today it's still seen as "bomb-proof" by the rest of the world, and is often used as a model. But it wasn't always that way...

When a massive ice storm took down 36,000 power pylons overnight in 1998, Quebec had to rebuild and restart their power grid from the ground up. Let's do some failure analysis and learn how big power systems around the world are designed to fail gracefully, and what happens when they don't. (P.S. TCP over power lines totally works)

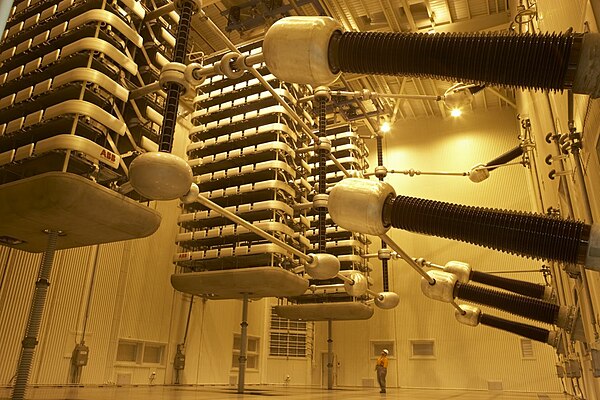

Nick Sweeting is the co-founder of Monadical in Montreal, and his favorite bike paths all run under power lines. He's a Django developer by day, and rogue internet archivist / power grid investigator by night. He likes learning about how big systems fail, and thinks thyristor halls look neat.

- 1min: intro, photos of james bay project

- hydro quebec origin story, now it has 20,000+ employees

- mega dams near the arctic circle + big wires

- modern distinct grid regions of North America

- (Quebec & Texas = independent)

- 3min: technical overview of power systems

- High-voltage 3-phase AC / phased power systems

- old school: transformers and fuses

- modern: capacitors + thyristors + optic coupling

- grid electricity uses a whole different set of tools and math from micro eletronics

- frequency syncronization, phase balancing

- Hz = spinning kitectic energy in the system

- distance measuring by bouncing a pulse down the wire and timing each impedance mismatch's reflected pulse

- 2min: HVDC, edison wins after all

- good for long distances grid connections with no step-ups / step-downs (Quebec sells lots of power to NY northeast USA)

- more efficient wiring, no skin effect

- rescue lifeline in blackout situations

- easier to control digitally (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Static_VAR_compensator)

- 2min: theres a whole world of network chatter on power lines

- channels are coupled on and off with capacitors, like radio

- signals get attenuated by transformers / capacitative loss / radio transmission losses (aka pollution)

- AM radio band for home entertainment radio stations

- ~100-500kHz: OSGP, IOT, home automation, meter reading

- ~9-500kHz: DLC MAC ethernets with IPv6 at 576 kbit/s for grid contorl and meter reading

- ≥ 1 MHz LAN: ethernet-over-power AC wall wart systems

- 2.4-6GHz BPL: long-distance broadband backhaul, but causes lots of interference because the grid is a massive antenna

- ≥100 MHz transverse mode: long-distance >1 Gbit/s connections, but interferes with astronomy and lots of other stuff

- 2min: how does this carry over to software?

- modular pieces with industry-shared common APIs

- it's a distributed system: time synchronization, leader election, back-pressure communication

- it's a critical system: graceful degradation, load-shedding, split brain avoidance, and staggered restart procedures

- it's an abstracted system: humans, politics, circular dependencies ("we cant start the database without the auth server running first" == "we cant start this natural gas power plant without grid power to spin up its compressors")

Altogether the reservoirs created by the James Bay Project cover an area of 13,341 square kilometers - the largest bodies of water ever created by humankind. One of the reservoirs, Caniapiscau, is the largest freshwater lake in Quebec.

In addition to the six 735 kV power lines that stem from the James Bay Project, a seventh power line was constructed as an 1,100 kilometres (680 mi) northward extension of an existing high-voltage direct current (HVDC) line connecting Quebec and New England. This power line expansion was completed in 1990. As a result, the direct current power line is unique because there are multiple static converter and inverter stations along the 1,480 kilometres (920 mi) long power line.[8] It is also the first multiterminal HVDC line in the world. The ±450 kV power line can transmit about 2,000 MW of hydroelectric power to Montreal and the Northeastern United States.

The pylons and conductors are designed to handle 45 millimetres (1.8 inches) of ice accumulation without failure,[19] since Hydro-Québec raised the standards in response to ice storms in Ottawa in December 1986 and Montreal in February 1961, which left 30 to 40 millimetres (1.2 to 1.6 inches) of ice.[50][51][52] This has led to the belief that Hydro-Québec TransÉnergie's electrical pylons are "indestructible".[53] Despite being more than three times higher than the Canadian standard of only 13 millimetres (0.51 inches) of ice tolerance,[54] an ice storm in the late-1990s deposited up to 70 millimetres (2.8 inches) of ice.[19][51]

In the North American ice storm of 1998, five days of freezing rain collapsed 600 kilometres (370 mi) of high voltage power lines and over 3,000 kilometres (1,900 mi) of medium and low voltage distribution lines in southern Quebec. Up to 1.4 million customers were without power for up to five weeks.

The 1998 ice storm in numbers:

- Up to 1.4 million households without power

- Over three million people affected

- 3,000 km of transmission and distribution lines rebuilt

- 400 km of high-voltage lines rebuilt

- 1,500 towers replaced

- 17,000 poles replaced

- 4,500 transformers replaced

- 88,000 insulators replaced

Changing the transmission system to create loops to deliver power over more than one path:

- Creation of the 735-kV Montérégie loop and the 315-kV downtown Montréal loop

- rearranging the system between Québec and Trois-Rivières to create the Québec-Mauricie loop

- Reinforcing the supply to downtown Québec

- Integration of the new 735-kV Bout-de-l’Île substation to the 735-kV greater Montréal loop

The Levis De-Icer is a High voltage direct current (HVDC) system, aimed at de-icing multiple AC power lines in Quebec, Canada. It is the only HVDC system not used for power transmission. In the winter of 1998, Québec's power lines were toppled by icing, sometimes up to 75 mm. To prevent such a damage, a de-icing system was developed.[1] The Levis De-Icer can use a maximum power of 250 MW; its operation voltage is ±17.4 kV. It can be used on multiple 735 kV AC power lines. An ordinary 735 kV line with a bundle of four 1354 MCM conductors per phase, requires a de-icing current of 7200 A per phase.[4] At −10 °C and wind velocity at 10 km/h, it would take 30 minutes of current injection on a phase to melt 12 mm of radial build-up of ice.

- https://news.hydroquebec.com/en/press-releases/1313/twenty-years-ago-quebec-was-battered-by-an-ice-storm/

- https://www.compusult.com/html/IWAIS_Proceedings/IWAIS_2005/Papers/IW09.PDF

- http://www.hydroquebec.com/data/transenergie/pdf/2019-12-31-liste-centrales-privees-raccordees-reseau-hydro-quebec.pdf

- https://www.iso-ne.com/about/key-stats/maps-and-diagrams/#system-diagram

- https://www.iso-ne.com/static-assets/documents/2016/07/New-England-Geographic-Diagram-Transmission-Planning-Through-2026.pdf

- https://electricity.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/CEA_16-086_The_North_American_E_WEB.pdf

- https://gotocon.com/dl/goto-aar-2013/slides/SebastianEgner_ProgrammingLanguagesAndThePowerGrid.pdf

- https://www.jamesbayroad.com/hydro/index.html

- https://openinframap.org/#9.14/45.5468/-73.7943 ⭐️ (great map of all the power lines and substations)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hydro-Qu%C3%A9bec

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Hydro-Qu%C3%A9bec

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hydro-Qu%C3%A9bec%27s_electricity_transmission_system

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_Quebec_history

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Bay_Project

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Bay_Energy

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert-Bourassa_generating_station

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_generating_stations_in_Quebec

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High-voltage_direct_current

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quebec_%E2%80%93_New_England_Transmission

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Lawrence_River_HVDC_Powerline_Crossing

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Champlain_Hudson_Power_Express

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Levis_De-Icer

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smart_grid

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Power-line_communication

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hydro-Qu%C3%A9bec%27s_electricity_transmission_system#Electricity_pylons

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nationalization_of_electricity_in_Quebec

- White Gold: Hydroelectric Power in Canada by Karl Froschauer (2011)

- Canadian Power Imports: Update on Electricity Imports in the Northeast ... by USA Gov. General Accounting Office (1989)

- The Power Grid: Smart, Secure, Green and Reliable edited by Brian D’Andrade (2017)

- The Grid: The Fraying Wires Between Americans and Our Energy Future by Gretchen Bakke (2016)

- Energy and Civilization: A History by Vaclav Smil (2017)

- Charging Ahead: Hydro-Québec and the Future of Electricity by Julie Barlow and Jean-Benoït Nadeau (2019)

- Hydro-Quebec: After 100 Years of Electricity by Daniel Larouche Bolduc, Andre, Clarence Hogue (1989)

- Power from the North: Territory, Identity, and the Culture of Hydroelectricity in Quebec by Caroline Desbiens (2014)

- Power Struggles: Hydro Development and First Nations in Manitoba and Quebec by Thibault Martin and Steven M. Hoffman (2008)

- Hydro-Québec and the Great Whale project: Hydroelectric development in northern Québec by Susan Williams (1994)

- Power from the North by Robert Bourassa (1985)

- Social and Environmental Impacts of the James Bay Hydroelectric Project by James F. Hornig (1999)

- The James Bay Project by Jill M. Johnston (2009)

- ELECTRIC RIVERS by Sean McCutcheon (1998)

- J’aime Hydro documentary theatre piece by Christine Beaulieu (2018)

- More reference books by Hydro Quebec...

Contact me on Twiter @theSquashSH for corrections or suggestions!

If you liked this, check out our full-stack software development consultancy Monadical.com!

You're welcome to use content from or portions of the talk,

as long as you give credit to both this talk and the relevant primary sources I cite.