Reduce Complexity and Accelerate Value Creation through Modularity - Modular Management

Modular Management is internationally regarded as the market leader in creating modular systems and configurable product architectures.

Our consulting solutions have been proven through hundreds of successful implementations in various industries, including home appliances, transport, power, construction, and telecom. We have shown that it’s possible to establish a competitive advantage if you create, implement and govern modular systems and product architectures.

Central to our offering is world-class technology for strategic, data-driven product management. Our cloud-based software for product architecture lifecycle management, PALMA, is built on an in-memory database platform. It's faster and more capable than anything else on the market today.

Do you want to master product complexity and accelerate business performance?

We have over 25 years of experience serving clients across the globe, mastering product complexity, and accelerating business performance. Our unique expertise, methods, and tools in Strategic Product Architecting and Modularity enable our success. Our proven methods and tools have been continuously developed and refined to ensure maximum efficiency and quality in execution.

PALMA is a cloud-based strategic software to create, document and operationalize modular product architectures. With its unique information model and structured approach, you can manage and analyze the digital weave of data and relations that defines your product offering.

All You Need to Know About Modularization

Modularization is the activity of dividing a product or system into interchangeable modules. The target of modularization is to create a flexible system that enables the creation of different requested configurations, while also reducing the number of unique building blocks (module variants) needed to do so. By re-using module variants across multiple configurations, volumes are consolidated on the module level, and economy of scale is reached without limiting/rationalizing the product offerings.

The benefits of a modularity approach are many. For example, a company can increase customer value by configuring the right product for the situation. The speed of development is increased because innovation is limited to one or a small group of modules in the system rather than a whole product. Additionally, internal complexity is reduced by limiting the number of variants to design, manufacture, and maintain the portfolio. This internal cost of complexity is often overlooked or widely underestimated in enterprises because it takes so much time, resources, and capital to maintain large numbers of parts.

Modularization combines the benefits of standardization, which drives a low cost of complexity, with customization by creating the right product for each customer and their situational needs.

Modularization captures the benefits of Standardization and Customization

While the most obvious examples of modularization might be physical products, the technique is just as useful within software and service products.

The main enabler of modularization is standardized interfaces. The interface allows one variant of a module to be interchanged with other modules to meet the required performance level and adapt to specific applications and/or functional needs of the product.

A Modular System is a group of modules, interfaces, and rules that enables the configuration of products. Success is built upon the ideas of flexibility, agility, and efficiency. A great Modular System will enable efficiency, of course, but it will also be flexible for a large scope of products and agile for future changes so the architecture can live for a long time. Read this post to gain further insight into what defines the best modular systems.

Efficiency for a Modular System means enabling an economy of scale and stability. By re-using modules across different products, volumes are consolidated. By isolating modules when changes are required, supply chains can benefit from long-term plans and commitments. For example, a battery system may include a cooling fan that can be common across all product variants. In our experience, this is the first trait of modularization that industry executives recognize.

Flexibility for a Modular System means enabling mass customization for specific customer needs. As an example, a battery system may be configured to provide different energy storage capacities. For SKU-driven businesses, Modular Systems enable faster SKU creation with less effort. For customized products, modularization helps highly efficient configuration tools to make quotes faster and more accurate. In many cases, the customer can configure the product herself in an online CPQ (Configure-Price-Quote) system.

Agility for a Modular System means allowing for swift and controlled changes for new requirements and/or technologies. For example, the charge control electronics may be upgraded to allow for optimized charging considering speed and green energy availability. By preparing for a change in geometry and interface specifications, changes can be isolated to specific modules, enabling the surrounding modules to remain untouched.

Companies that succeed in creating Modular Systems, systems that tick all three boxes, outperform the competition regarding customer value and cost. It affects the whole business; Sales, R&D, Production, Sourcing, After Market, and everywhere else where the product complexity impacts margins, costs, and speed.

Modularity is a measurement of how well a system performs given the business strategy and targets set. Those targets can generally be defined as efficiency, flexibility, and agility. Thus, the measurement of modularity will vary with what is most important to the specific business. Some measurements will be more important than others given the targets set for the modularization program.

To measure efficiency we can create a measurement of how many different building blocks are needed in the system. The fewer, the better. An excellent proxy for efficiency is part number count (PNC). By controlling part number counts, managers can ensure that complexity is not added over time unintentionally. It also becomes much easier to measure the impact of any new parts that are added intentionally to expand share or improve the offering. In many companies today, PNC expansion/reduction and its impact are poorly understood, leading to margin decline.

To measure flexibility we can use a measurement of how many configurable products are available to sell given a fixed set of module variants. This measure is often called configurability and defines as the number of possible products divided by the number of components (PNC) needed.

To measure agility we can measure the number of new components required to increase the product offerings. This is typically measured over a period to get an average reading, for example annually. The definition of the metric is the number of introduced components divided by the number of enabled product variants.

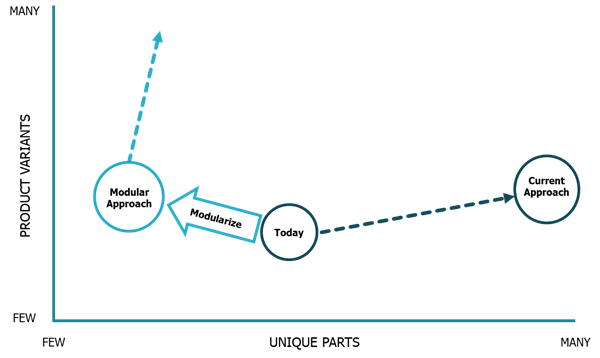

Chart illustrating how modularity is creating flexibility while reducing complexity

Leif Östling, former CEO of Scania, has said:

“Control and limitation of part numbers is one of the most important factors to optimize profitability over time.”

While proof of Modularization can be traced as far back as the Terracotta Army (200 BCE), modern industrial use of modularization was pioneered by leaders in different industries such as Scania, Toyota, Nippondenso, Dell, and Sony. These companies managed to take clear market leadership using modularization, governing, and improving their Modular Systems over time.

In Germany, modular systems are often called Baukasten, a term literally translated to construction set. Volkswagen, for example, calls their modular systems Baukasten, e.g., Volkswagen MQB, which stands for Modularer QuerBaukasten_,_ roughly translated to Transversal Engine Modular System. Baukasten was frequently used as a term in the 1930s for do-it-yourself kits, such as model railways, modular radios, and electronics toolkits for kids. These toys have much in common with industrial modular product platforms. They have the same target to create flexibility and the same means - standardizing interfaces.

Sony utilized modularization in a structured way for both the Handycam and Walkman product lines to continuously stay ahead of the competition throughout the 1980s. As soon as competitors caught up, Sony could immediately launch the next version and again be the product leader.

Scania, on the other hand, understood that modularity was the way to enable mass customization. By creating a modular system for the truck on different levels, an almost infinite number of variants could be configured and manufactured on the same assembly lines without costly changeovers. For decades Scania’s unique focus on modularity enabled them to outperform the competition in profitability (2X to 5X), even though their volumes were lower than some competitors. By optimizing variance and customization, Scania successfully reached an excellent economy of scale while simultaneously providing individual drivers with the exact truck they desired.

In today’s modern economy, successful companies are champions of modularity in hardware, software, products, and services. With the birth of Web 2.0, modularity reaches across company barriers. Today, micro-services, web apps, and open APIs enable a whole new set of customization possibilities. And as more functionality transitions from hardware to software, traditional hardware companies can also benefit from adopting new ways of thinking and working.

Many companies suffer from complex software development such as:

- Difficulty in scaling the development capacity

- Software is driving quality problems even though the testing efforts are high

- Difficulty in planning and budgeting software development since changes lead to unforeseen ripple effects

Three typical root causes for software architecture problems are “Developed by me” software, highly coupled software structures, and multiple overlapping software platforms.

Even companies that traditionally have been focused on mechanics are becoming software companies whether they like it or not. CTOs of “hardware companies” are realizing that they often have more software engineers than hardware engineers.

By making software modules independent, reusable, and interchangeable, development can be much more efficient and truly agile. Independent modules make development teams autonomous for improved efficiency and time to market. Read more about Strategic Software Modularization and download our template for documentation of a strategic software module.

A Module is a functional building block with specified interfaces driven by company-specific strategies.

A modular system is a collection of building blocks that can be configured in different ways, adapting to different customer needs. Modular Systems can be hierarchical because modular sub-systems can be shared across more than one modular product architecture. Modular Systems can have one or more architectures which are the structures that describe how products are built with the modules.

A Modular Product Architecture is a geometrical and logical structure for building a type of product based on a Modular System. For example, a company can use one Modular System for both washers and dryers. However, the washers and dryers have different Modular Product Architectures.

Modularization is the activity of subdividing a system of products into modules. Modularization can act on any combination of hardware, electronics, software, and services.

A Module Variant is the realization of a Module, fulfilling its interfaces and strategic intention. For hardware and electronics, it is a physical part. In software, it is an encapsulated piece of code. Software modules typically have only one realization that is flexible for all use cases. For hardware and electronics, each module will have one or more variants.

A Module Interface defines how a Module interacts with its surroundings. The interface can be with other modules, but also with the external world. An interface can be physical, attaching one module to another. It can specify how information, media, or power is transferred between two modules. It can also be geometrical, defining the space reserved for the module.

A Configuration is a specific combination of module variants according to a Modular Product Architecture that fulfills a set of configuration rules.

Configuration Rules

Configuration Rules govern how a product is allowed to be combined from a set of module variants. The Modular Product Architecture describes structure, how the product is built. The Configuration Rules describe the logic for what module variants can be combined and define how customer needs are translated to a suitable configuration. Configuration rules can also control business logic. For example, the packaging and the pricing of products and features.

A Product Configurator is a software solution that executes configuration rules. It can be customer-facing in the form of a sales configurator/CPQ solution. But a Product Configurator can also be used internally to create bills of material for production, and engineering, or to automatically generate drawings for customizable products.

The Cost of Complexity is used to describe the expenses caused by introducing new offerings and managing the variety of products produced. Many different products would cause a high cost of complexity. Whereas fewer and more similar products result in a low cost of complexity. In essence, it is a way to understand the economy of scale and how products affect it. Modularization can be used to improve the economy of scale while keeping configurability in the products. Scale is reached on the module level rather than on the product level resulting in a better market offering with far fewer parts.

A product platform is a collection of similar products that are grouped to enable cross-product sharing of certain components. Product platforms often can become rigid and inflexible when new or different customer adaptations are required. Platforms are also more difficult to enforce the re-use of components across product lines. Note: Modularization and a Modular Platform can be used as a synonym for a Modular System. Volkswagen is a great example of transitioning from products to platforms to modular systems.

The Advantages of Modularization | Techwalla

By Luke Arthur

Techwalla may earn compensation through affiliate links in this story.

Developers often use modularization as a way to simplify their coding. With modularization, the coding process is broken down into various steps instead of having to do one large piece of code at a time. This method provides developers with a number of advantages over other strategies.

One of the advantages of using this strategy is that it breaks everything down into more manageable sections. When creating a large software program, it can be very difficult to stay focused on a single piece of coding. However, if you break it down into individual tasks, the job does not seem nearly as overwhelming. This helps developers stay on task and avoid being overwhelmed by the thought that there is too much to do with a particular project.

Advertisement

Video of the Day

Another advantage of this strategy is that it allows for team programming. Instead of giving a large job to a single programmer, you can split it up into a large team of programmers. Each programmer can be given a specific task to complete as part of the overall program. Then, at the end, all of the various work from the programmers is compiled to create the program. This helps speed up the work and allows for specialization.

Advertisement

Modularization can also improve the quality of a piece of code. When you break everything down into small parts and make each person responsible for a certain section, it can improve the quality of each individual section. When a programmer does not have to worry about the entire program, he can make sure that his individual piece of code is flawless. Then, when all of the parts are combined, fewer errors are likely to be found overall.

Advertisement

Modularization allows you to reuse parts of programs that already work. By dividing everything up into modules, you break everything down to the basics. If you already have a piece of code that works well for a particular function, you do not have to reinvent the wheel. You simply use the same code again and let the program rely on it. This can be done repeatedly throughout the program if the same features are needed again and again. This saves programmers time and effort.

Modular Languages

The following languages officially support modularization (in the order of their release years; the list isn’t complete): IBM RPG (1959), COBOL (1960), PL/I (1964), ALGOL (1965), ML (1973), Modula (1975), Ada (1980), Common Lisp, MATLAB, Objective-C (1984), C++ (1985), Erlang, Object Pascal (1986), Oberon, Perl (1987), Fortran-90, Haskell (1990), Python (1991), Java, Ruby, JavaScript (1995), OCaml (1996), C# (2000), D (2001), BlitzMax, eC (2004), F# (2005), Closure (2007), Go (2009), Rust (2010), Dart, Elixir (2011), Elm (2012), F (2014), NEWP (2015). All but four of them have been developed after C. It would be unfair to blame C for not being modular.

One increasingly popular language that supports modularization by design is Python. Creating a module in Python is ridiculously easy: any Python file is already a module. The name of the module is the name of the file, less the py extension. For example, file jsontool.py here contains a module called jsontool. If you’ve ever written any file in Python, you’ve written a Python module.

To (re)use a module in your Python program, you must import it with one of the following statements:

import jsontool

from jsontool import json_read # import just json_read

from jsontool import * # import everything

The three key differences between a C file and a Python module are:

To refer to a Python module’s object from outside that module, you usually use its fully qualified name, which consists of the module name and the object name. Function read_json from module jsontool is known as jsontool.json_read unless you use the from form of the import, which is also possible but not advised. You may have more than one function with the same name defined in different modules. For example, you may have a family of input/output modules (such as json, xml, and csv), each having the functions read and write and providing a consistent and easily memorizable interface. The qualified names are a blessing. In C, all names are flat, they end up in the same name space.

The second difference is both a blessing and a curse. Unlike C, Python is a dynamically typed language: the type of a variable or a value returned from a function is determined at runtime and can be changed. The good news is that you don’t need a header file to ensure that the caller’s expectations of a function match its implementation. No such mechanism even exists in Python! The bad news is that the caller won’t know if the module’s implementation changed, potentially leading to inconsistency. As you already know from the example here, the inconsistency will likely manifest itself at runtime, when it’s already too late to fix it.

To end on a positive note: the third difference is also in favor of Python modules. Any C program must have the main function. Any reusable C file must be combined with another code fragment (often called a driver). The driver provides the main function that calls functions from the file — say, for testing purposes. Not that writing a driver is a big deal, but it’s tedious and inflexible. A Python module may have a dual nature: when imported from another unit, it’s a module (a collection of functions and variables) but when called alone, it’s a complete program.

This duality is accomplished by having the variable __name__. The value of this variable is automatically set by the Python interpreter (python itself). When another module imports the module, __name__ evaluates to the imported module’s name. Otherwise, it evaluates to “__main__”, a not so subtle reference to C’s main function. The bottom of jsontool.py might look like this:

# All functions and variables are somewhere above ^^^^^ def main(): # Do all business logic — or testing! — here pass if __name__ == ”__main__”: main()